Is Privatization of Resettlement Land Viable in Zimbabwe? Land Tenure Policy Considerations

Freedom Mazwi1 & George Mudimu2

- University of Zambia

- Collective of Agrarian Scholar- Activists from the Global South (CASAS)

Introduction

On the 8th of October 2024 the Zimbabwean state announced plans to issue private title on land held by Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) land beneficiaries. The announcement was met with excitement by certain analysts, civil society and political actors from across the political divide. This intervention is aimed at examining policy implications and to offer policy alternatives on the proposed ‘private title’.

Many analysts see the issuance of private title as way to unlock the value of land. This position is largely derived from Hernando de Soto, a Peruvian economist, who argued that while assets such as land can be leveraged on the market, they often lack formal legal documentation rendering them “dead capital”. Therefore, the Zimbabwean state position is based on the perception that the issuance of private title to land will render it ‘living capital.In this intervention as, has been argued in several other countries in the global South, we argue that such a position lacks on many fronts as it negates the history and context of Zimbabwe in relation to the land question. We posit that while freehold tenure thrives in several countries in the global North, it’s not a solution for several countries in the global south especially African countries. Private tenure which is embedded in property rights is a western concept with strong ties to the Roman-Dutch law and John Locke’s Two Treatise of Government in 1689. Private property rights aka Freehold was weaponized to expropriate land from native Africans during colonialism. Through the freehold mechanism, white minority economic and political interests were entrenched, which fostered and entrenched, inequalities and unequal development within African colonial states.Therefore, ongoing attempts to privatize land go against genuine calls for decolonizing land tenure systems that are increasingly gaining momentum among progressive political and intellectual circles. The next section provides a background of Zimbabwe’s land reforms and changing tenure systems.

Zimbabwe’s Land Reforms & Tenure Systems: A Brief Overview

Blacks in colonial Rhodesia experienced massive land alienations with the white settler population benefitting and being settled on fertile large-scale commercial farms (Moyo 1995). This laid a basis for an armed liberation struggle thus culminating in the attainment of independence in 1980. At independence, the postcolonial state inherited a bi-modal tenure agrarian structure mainly composed of freehold tile held by white-large scale commercial farmers on one hand, and customary tenure held by black confined to Communal Areas (Moyo 1995). With agricultural production being generally stable from 1980 to 1999 many analysts attributed this to white large-scale commercial farmers’ “capacity” and ingenuity while some acknowledged their ability to access credit from private commercial banks. The late Professor Sam Moyo, however, pointed out that food security during this phase was largely driven by the resilience of underfunded black communal farmers. The ability to access commercial loans by white commercial farmers using freehold title is part of the reasons why many believe that recent policy pronouncements on tenure reforms can improve access to agrarian finance. From 2000, Zimbabwe initiated a radical Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) which apart from transferring land held by white commercial farmers to landless and land short peasants also challenged property rights by dismantling freehold tenure and replacing it with state based tenure (Moyo and Chambati 2013).In response, international capital went on strike (ibid), and the country was placed on economic sanctions leading to major declines in agricultural credit and production volumes (Moyo and Nyoni 2013; Binswanger-Mkhize and Moyo 2012). These responses by global capital and hegemonic forces were aimed at discouraging other countries from embarking on a similar radical land reform path. And this to an extent has been witnessed by several stalled expropriation without compensation demands for land in South Africa, Namibia among many other African countries with serious land questions. The economic hardships that the country had to endure over the past two decades is partly attributable to international isolation although we must be quick to point out that other internal dynamics were also at fault. We have attended to these internal dynamics in our previous discussions (Mazwi and Mudimu, 2019).

With polarity escalating emanating from the land reform, the state maintained that the land reform was irreversible and legislated state-based tenure (A1 permits and 99-year leases) which cannot transacted on markets to forestall land sales. However, by 2017 it was becoming increasingly clear policy shifts were underway (Mazwi and Mudimu 2019). Joint ventures between black resettled farmers and former white large-scale commercial farmers as well as land rentals were now actively being promoted by the state among many other forms of partnerships (see Mazwi 2022; Mudimu etal 2021). This reflected the limitations of radical land reforms in a neoliberal era and was largely unsurprising given international financiers, right wing intellectuals and civil society were at the forefront in discouraging state-base tenure and other forms of support for resettled farmers by the state. To some extent, the state capitulated to such forces although it must be stated that some voices internally as represented by the veterans of the liberation struggle have raised their voices against such maneuvers. Economic liberalization was offered in the agrarian sector and this had to be led by the private sector on the backdrop of liberalizing land tenure systems and minimum state support to the resettled farmers as well as to abandon state support for farmers in favour of a private sector led agricultural pathway.

Zimbabwe has various forms of land tenure. Rukuni (2012) sums up the major forms of land tenure in Zimbabwe as follows:

- Freehold (also known as private holding for large scale commercial farmers and some small scale

- Short term leases

- 99-year lease A2

- Offer letter A1

- Customary tenure;

Closely linked to the forms of tenure is what is termed the basket of rights (Rukuni, 2012). The rights basket is:

- Use rights; permission to grow crops, trees and make permanent improvements such as housing.

- Transfer rights; sell, give, lease, rent.

- Exclusion rights, exclude others from using or transfer

- Enforcement; legal judicial or institutional provision to guarantee exclusivity and resolve disputes.

In the next section we discuss the implications of liberalizing tenure systems.

Land Privatization Implications: Lessons from Africa

Proponents of freehold argue that it enables farmers to access agricultural credit and also stimulates agricultural investments. Such proponents include multilateral institutions, scholars, and African policy makers who have been advancing privatization of tenure. To date, over two dozen African countries have proposed de jure land law reforms that are extending the possibility of access to formal freehold land tenure to millions of poor households (Ali et al 2014:1). Notable examples include Zambia in 1995, Uganda in 1998, Côte d’Ivoire in 1998 and 2015, Malawi in 2002, Kenya in 2012, Mozambique in 1997 and 2007 and Tanzania in 1999 and 2015. The objectives explicitly aim to clear the way for full privatisation and commoditization of farmland. Based on experiences from other African countries that have privatized peasant farmers land in attempt to boost agricultural investments we contend that Harare’s attempt to introduce freehold tenure is very much unlikely to enable access to agricultural loans. Research has shown that peasant farmers in countries such as Namibia, Ghana and Kenya have faced difficulties to access loans from banks even with their land having been privatized. In Kenya, Issa Shivji demonstrates uneasy relations between financial institutions and peasants. In an interview with Marc Wuyts, Issa Shivji notes;

Or, as happened in Kenya, the Banks cannot enforce foreclosure simply because the bailiffs would be chased away by spear-wielding peasants or, as happens more often, they find the situation on the ground to be very different from that in the land registry (Wuyts and Shivji 2008).

These observations reveal the complexities and intricacies surrounding the land individualization and titling. Establishing a land register is an expensive process and countries that have tried to privatize land have found it difficult to establish a credible register. For Zimbabwe, this is likely to be a mammoth task considering the shambolic nature of the Land and Information Management System (LIMS) (Moyo and Maguranyanga 2014). There are also other pressing developmental challenges such as health, education, infrastructure and industrialization that remain priorities ahead of the individualization of title.

Elsewhere, we have presented compelling evidence using Zimbabwe’s experiences challenging conventional ‘wisdom’ on the nexus between agricultural financing and tenure systems (see Mazwi 2022). The scramble to finance FTLRP land beneficiaries whose tenure relations are mediated through the state in crop commodities such as tobacco and sugar is indicative of how global demand on markets tends to shape access to finance by peasants and not necessarily the land tenure regime. Arrangements such as contract farming and joint ventures are formats used by international capital to finance production post 2000, and although they tend to be characterised by unequal power balances and exploitation in favour of capital, they have proceeded successfully without the ‘private’ tenure in place. A similar pattern is also reflected in other countries like Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Ghana where international capital is in partnership with the peasantry on lands held under customary tenure for export oriented crops (see Martiniello 2024; Sulle 2016; Torvikey et al 2016). All this shows that profits are a major motivating factor ahead of tenure form in agricultural partnerships in contemporary times.

Growing evidence suggests privatization of tenure leads to land concentration and alienation (see Moyo 2007; Moyo 2016; Chambati, Mazwi & Mberi 2017; Martiniello 2017; Tsikata et al 2014; Shivji 2023). This occurs when capital (foreign and domestic) in alliance with local elites consolidate landholdings and encroach into lands held by poor peasants taking advantage of farmers who are in most cases precarious due to limited state support and therefore vulnerable to land concentration by capital. Overall, land sales are attributable to distress sales, economic recession, bad harvest, illness or death in the family, or calamity, and through mortgage default. In the United States, and much of Europe the absence of explicit market restraints against foreclosure and eviction safeguarding the homes and property of the poor leads to massive land consolidation by capital (Boone, 2018). By naturemarkets offer many chances for opportunistic behavior, and tend to favour strong market actors, that is, those with the capital, know-how, and information to protect and expand their property rights, and to buffer themselves against risk (ibid). The late Professor Sam Moyo in his work on the impacts of neoliberalism noted the presence of land concentration in postcolonial Africa (see Moyo 2007). He observed that with the individualization of tenure under Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) policies, the amount held by small-scale farmers was on a decline at a continental scale, while land held by foreign entities and domestic capitalists was increasing leading to massive land inequities (see Moyo 2016).In Uganda, Martiniello (2017) shows how landholdings by small-scale sugar outgrowers were decimated by local elites with financial means at Kakira works sugar plantations. A similar phenomenon is also observed in Mozambique among sugar out growers driven were land sales are on the increase (Chambati, Mazwi & Mberi 2017).

These land transactions perpetuate hunger and poverty with women and children being the worst affected (Mazwi etal 2022). Evidence suggests that it is mainly males who sell the land without consulting their female spouses and rest of family members. The impact on women is likely to be worse for Zimbabwe where research shows that about 80 percent of the plots were registered in the names of males (Moyo et al 2009). Resulting from land sales, small-scale farmers end up selling their labour to neighboring farmers, a livelihood strategy which does not guarantee enough income for self-sustenance. The land sales also leave generational poverty on the shoulders of children of poor small-scale farmers. Issa Shivji notes that much of the political violence that was witnessed post-2007 in Kenyan elections was intricately linked to land inequalities, exacerbated by the privatization of land. Given the foregoing, it is imperative to consider the potential socio-economic and political ramifications of the intended policy of privatizing resettlement land. In the following section we consider some policy options.

Policy Options

This intervention also acknowledges the challenges associated with the current state- based tenure in Zimbabwe. One key challenge has been allocating the central state great powers with regards to land control and ownership thus leaving land beneficiaries very uncertain about the security of tenure. The intensification of land evictions since 2017 at the behest of capital and politically powerful elements within the state is one manifestation of the central state either failing to control the situation or the system becoming open to abuse. Looking from a different perspective the obtaining situation leaves various stakeholders who include financial institutions, development partners and farmers with little confidence in the tenure system. Without thinking or considering the privatization of tenure, a number of options that bring confidence in the land and agriculture sector need to be considered.

- 1 Devolving Land Management from the Central State to the Zimbabwe Land Commission.

It is our view that land management and administration must move away from the central state to an already established constitutional body mandated to deal with land affairs known as the Zimbabwe Land Commission (ZLC). The Zimbabwe Land Commission must be given autonomy like other constitutional bodies such as the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission and the Zimbabwe Gender Commission. For purposes of accountability the Zimbabwe Land Commission (ZLC) must be accountable to parliament. The commission must be provided with human and financial resources to manage the Land and Information Management System which must be audited and made to a wider public and financial institutions for purposes of transparency and accountability. The institution must be decentralized up to the district level so as to capture the most reliable information. Government institutions such as the Ministry of Lands, Ministry of Local Government, traditional authorities and civil society organizations can constitute advisory committees that can be established up to the district level.

- 2 99-Year Lease Documents as a form of Tenure

The dangers of privatizing tenure are not worth pursuing as argued in the previous sections. There is a social, economic and political prize to be paid by individualizing tenure. We have also shown that the financial benefits are often exaggerated by international financial institutions and neoliberal analysts. The issuance of freehold title is also not consistent with decoloniality which the FTLRP was all about. Mamdani (2008) concretely elaborated that the FTLRP symbolized a decoloniality project to complete the unfinished business of the liberation struggle. We see 99- year lease documents managed by a semi-autonomous Zimbabwe Land Commission as the best possible form of tenure for middle- to large scale A2 farms. A1 farmers can be granted A1 permits which will still be managed by the Zimbabwe Land Commission. The administration of these documents by the ZLC will go a long way in building certainty and confidence in the land and agrarian sector.

- 3 Joint Ventures Partnerships

To boost levels of investment and agricultural production on farms, joint venture partnerships between farmers and capital must remain permissible. These ventures must be approved by the Zimbabwe Land Commission and must protect small scale producers especially in the face of unpredictable global market changes

- 4 State Agrarian Support

The state must provide agrarian support to land reform beneficiaries on friendly terms and not pursue pseudo inputs schemes. This agrarian support must embrace technology and mechanization programs.

- 5 Participative Decision Making

The move to unilaterally privatize landholdings in land reform areas demonstrates minimal or low consultation with wider stakeholder including grassroots farmer organizations. As a way forward it will be imperative that the state does serious and democratic consultations with all stakeholders especially land reform beneficiaries.

- 6 Endogenous Development

The Zimbabwean state, in as much as the world is now globalized there is an urgent need for it to pursue homegrown economic solutions that place the poor and marginalized communities at the center of development processes. The neoliberal inclined policies that regard external actors as experts and technocrats therefore they know best has failed especially when it comes to issues of land tenure in Zimbabwe.

References

Chambati, W., Mazwi, F. and Mberi, S(2017). Contract farming and peasant livelihoods: the case of sugar outgrower schemes in Manhica District, Mozambique. Harare: SMAIAS Publications.

Mazwi, F (2022). The Political Economy of Contract Farming. Cape Town, HSCRC Press.

Mazwi, F (2022). Joint Ventures and Land Rentals in Tobacco: Limitations of Radical Land Reforms in a Neoliberal Economic Environment- the case of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studies, DOI: 10.1080/03057070.2022.2048553

Mazwi, F., Mudimu,G.T & Helliker, K (2002). Capital and the Peasantry in Southern and Eastern Africa: Neoliberal Restructuring. Geneva, Springer Press.

Martiniello, G. (2017). Bitter sugarification: Agro-extractivism, outgrower schemes and social differentiation in Busoga, Uganda. Paper presented at 5th International Conference of the BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies. October 13-16. RANEPA. Moscow.

Mazwi, F., & Mudimu, G. T. (2019). Why are Zimbabwe’s land reforms being reversed? Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 54, No. 3. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/why-are-zimbabwes-land-reforms-being-reversed

Moyo, S.(2007). Land in the Political Economy of African Development: Alternative strategies for development. Africa Development,4, XXXII, 1-34

Moyo, S. (1995). The Land Question in Zimbabwe. Harare: SAPES Books.

Moyo , S (2016). State of family farming in sub-Saharan Africa: Its contribution to the rural development, food security and nutrition. Global Dialogue on Family Farming, FAO. 27-28 October. Rome.

Mudimu, G. T., Zuo, T., Shah, A. A., Nalwimba, N., & Ado, A. M. (2021). Land leasing in a post-land reform context: insights from Zimbabwe. GeoJournal, 86, 2927-2943.

Rukuni. M. 2012. Why Zimbabwe needs to maintain a multi-form land tenure system. Zimbabwe Land Series. Harare

Torvikey, D. G., Yaro, J. A., and Teye, K. J. (2016). Farm to factory gendered employment: The case of blue skies outgrower scheme in Ghana. Journal of Political Economy 5 (1): 77-97.

Tsikata, D, and Yaro, J. A. (2014). When a good business model is not enough: Land transactions and gendered livelihood prospects in rural Ghana. Feminist Economics. 20 (1). Wuyts M and Shivji I (2008) Reflections—Issa Shivji interviewed by Marc Wuyts. Development and Change 39(6):1079-1090.

kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbetThe “Just in Time” Explosion of Pagers and the New Technologies of Death

By Deivison Faustino and Walter Lippold

Translated by Adilson Skalski Zabiela

Originally published in Portuguese at Boitempo’s blog

How is it possible, and what does it mean, that pagers and walkie-talkies exploded simultaneously in Lebanon? We are at one of those historical moments that can be considered a “point of no return”: widespread climate collapses, mass unemployment intensified by artificial intelligence (AI), the platformization of politics under the technical and ideological hegemony of the far right, and the frightening sophistication of death technologies. We urgently need to discuss the geopolitical dimension and the material basis of electronic and digital technologies.

Last Tuesday, the world was surprised by the news of a terrorist attack carried out by the State of Israel that injured over 2,800 people and killed twenty[1]—including Syrian and Lebanese civilians and militants of the paramilitary Islamic party Hezbollah—through the coordinated explosion of AR-924 model pagers. The devices were distributed by the organization itself to militants to avoid interception of their cell phones, something known to be possible since the mass digital surveillance revelations offered by Snowden regarding Project PRISM in 2013. There is at least one child victim: nine-year-old Fatima Abdullah, who was hit by the explosion in the village of Saraain, Lebanon[2].

The next day, while we were distracted by the illegal return of X (formerly Twitter) to the Brazilian internet, the world was again surprised by news of new fatal explosions in Lebanon, this time involving IC-V82 VHF walkie-talkies manufactured by the Japanese corporation ICOM Inc., also used by Hezbollah militants and Lebanese state authorities. There are reports of other devices, such as solar panel systems that exploded in the Lebanese organization’s bases, as well as photos of biometric identification devices[3]. What is happening? How is this possible, and what does it tell us about contemporary capitalist geopolitics and its infrastructural basis? In Digital Colonialism: For a Hacker-Fanonian Critique[4], we draw attention to the centrality of the material and infrastructural dimension of digital technologies. Without disregarding the decisive importance of the logical layers and internet applications for understanding the ongoing social transformations, we argue that the digital is also real (material) and, therefore, subject to the causal laws of physics and political economy:

Contrary to intuition, the virtual is not the opposite of the real nor can it be confused with the digital. The digital is the storage and processing of data in computers in the form of codes representing letters, numbers, images, sounds, etc., while the virtual is a potential attribute of reality that can be grasped by the work of thought. (Faustino, Lippold, 2023)

At the same time, we try to demonstrate that, with the rapid development of digital technologies, contemporary wars have new and more effective technologies of destruction and death that allow a new repertoire of cyberattacks both on virtual environments (surveillance and espionage) and physical ones (attacks on military and nuclear facilities). We know that “the Government’s Robocop is cold, feels no pity…” (Racionais MC’s, 1997). The study of the cyborgization of war and its peak development with the introduction of drones on the battlefield is not new (Chamayou, 2015). However, the Palestinian genocide—the first genocide accompanied and ignored in “real time” via the internet—has prompted us to revisit the implications of these innovations for forms of surveillance and mass murder. More than that, it raises the suspicion that we are facing a new sociotechnical level of genocide practice, which demands attention.

The Sociotechnical Conditions of Genocide

Far from a technophobic stance but attentive to the different ways humans use technical and social means to meet certain needs, it must be recognized that in capitalism, the development of productive capacities ends up being directed more toward human self-destruction than toward satisfying needs.

From Portuguese and Spanish expropriation of Indigenous lands to the genocide of the Herero in Namibia, from the Nazi Shoah against European Jews to the current Palestinian genocide committed by the State of Israel, the development of sociotechnical means has represented an expansion of the capacity to kill. Mass murder is not possible without the existence of a massive death industry that always integrates the most sophisticated weaponry and informational technologies.

“We can begin to show the relationship between large corporations and the destruction of freedoms by looking at the Nazi period. There is consistent evidence of the decisive importance of IBM’s Hollerith punch card technology for executing the Holocaust. IBM codes were engraved on the arms of Nazi prisoners and allowed the identification, selection, and massive control of the extermination process. But the current and persistent demolition of rights is not as evident as that practiced during the Nazi period.” (Silveira, 2015, p. 12).

Some recent examples are the use of the Lavender AI in selecting Palestinian targets based on data profiling collected from digital platforms provided to the Israeli army, and the dissemination of viruses in enemy military installations. News of AI use in wars has been increasingly frequent, as have cyberattacks, and the first with great destructive potential were executed by the Stuxnet, Flame, Duqu, and Gauss viruses, used in the early 2010s to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program.

In terms of cyberweapons and electronic warfare, Israel is a technological vanguard that uses Palestine, but also Lebanon and Syria, as a nefarious laboratory to develop and showcase its latest-generation weapons. Some examples are the Scorpius electronic warfare device and the Harop drone from Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI)[5], as well as the Lavender AI—produced by Unit 8200[6]—and Pegasus, the infamous spyware negotiated by the Bolsonaro government with NSO, an Israeli company.

The ability to disseminate technology, even that considered obsolete, allows innovation in attack techniques. It is certainly an act of state terrorism that, despite all media ideology, dehumanizes the targets to revel in the efficiency of the attack. We have heard the term “surgical war” since 1991, with the invasion of Iraq and later the wars in the former Yugoslavia. These terms aim to delude public opinion into thinking that only the “bad guys” will be neutralized, within the U.S. Manichaean logic. “Project power without projecting vulnerability” (the motto of dronification and many remote attacks) (Chamayou, 2015). What we have actually seen is precisely the precision in destroying civilian lives, public facilities, and vital infrastructures in enemy territory.

But what does this have to do with pagers and walkie-talkies tearing apart militants and civilians on the streets of Lebanon? Since Snowden’s revelations, it is known that cell phones are vulnerable. Mobile devices can be monitored by political agents of all kinds for data collection purposes that allow for targeted propaganda, behavior profiling, and even georeferenced location of military targets. The subversive militant who ignores this technical reality—in war contexts of high geopolitical interests—is, above all, an easy target.

Concern about this fact increased in Palestine when it was revealed that Israel was using artificial intelligence programs to select possible targets for automated military drones. The AI program scanned social networks in search of keywords considered subversive or users’ contact with members of enemy political/military groups to eliminate them.

Once identified and selected, targets were tracked by facial biometrics and instant geolocation—provided by their cell phones—to then be attacked. If there was a target in a ten-story building, the entire building would be—and was—bombed. This process not only decimated tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank but also wiped these cities and their physical infrastructure off the map.

With this scenario in mind, Islamic leaders began seeking alternative means of communication. As far as is known, Hezbollah leaders prohibited their cadres from using cell phones and offered pagers and walkie-talkies as an alternative—which are still widely used in countries where access to cutting-edge informational technology is still a privilege of a few[7]. But the Islamic organization did not count on a completely unexpected factor: the possibility of Israeli intervention in the mobile devices’ production chain.

The pagers and walkie-talkies exploded, injuring thousands and killing more than ten people in the first wave, fourteen in the second, leaving hundreds in critical condition with severe injuries, putting the Lebanese population in panic. Rather than a cyberattack that hacked device hardware to overheat them or batteries programmed to explode after a certain cycle, we can call it an operation of logistical infiltration for sabotage.

But How Was This Possible?

Much remains to be explained, but apparently, we are facing sabotage in the supply chain of parts and components of pagers, supposedly manufactured by Gold Apollo, from Taiwan. The company soon announced that this batch was made in Budapest, Hungary, by BAC Consulting KFT, an acronym from the name of its founder and CEO, scientist Cristiana Bársony-Arcidiacono. The Orbán government denied that the pagers were in Hungary[8] and that BAC is only a commercial intermediary[9].

Initially, it was suspected to be a cyberattack that hacked the devices’ hardware to overheat them or that the batteries were programmed to explode after a certain cycle. The AR-924 pagers have a lithium battery that lasts 85 days, rechargeable via USB, so they are used not only by militants but also by civilians due to constant power outages[10]. But it’s unlikely that they all discharged at the same rate for thousands of people.

The most probable scenario is that a charge of one to three grams of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) was injected into the lithium-ion battery or a component of the board at the behest of Israeli intelligence during the manufacturing process at some point in the supply chain[11]. Probably, the synchronized explosion was remotely triggered via radio signal.

This differs from the historic Stuxnet attack, recognized in 2010, where cyber technology sought kinetic effects. The target of Stuxnet, produced by the United States and Israel, was to control the digital programs of uranium enrichment centrifuges in Iran. But the plan backfired, according to the documentary Zero Days[12] (2016); the virus, with modifications made by Israel, got out of control and ended up infecting the digital logistics chains of the attacker itself, in this case, the USA.

The transition from cybernetic to kinetic is not simple. If it were, with the advancement of the Internet of Things (IoT), it would be possible for smart refrigerators, smart lamps, smart devices controlled remotely with AI to become weapons of war. Perhaps it already is if we agree that technology is war and politics by other means, but here we are not dealing with a weapon in the sense we are analyzing in this article.

It’s important to remember that, although they work together, electronic warfare differs from cyber warfare. The first signs of electronic warfare were in 1899, in the Anglo-Boer War on African soil, with interference in Morse code transmission via telegraph. Later, with the use of broadcasting in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, they began using jamming or interference in radio wave transmission, disrupting radio signals. Fanon, in Sociology of a Revolution (1959), analyzes the jamming used by French colonialists to attack broadcasts from the rebel radio “The Voice of Fighting Algeria.” We can say that electronic warfare and colonialism are old acquaintances.

This type of attack, which aims to hit soldiers and militants through their equipment, killing or severely injuring them, resembles the use of so-called “spiked ammo,” or explosive ammunition, which was infiltrated through the supply chains of state and non-state actors. When triggered, the ammunition explodes the weapon and the hands of the operator. Weapons like rifles, grenade launchers, and mortars are the most known for applying this type of sabotage. The spiked ammo technique was first used by the English in Africa, in the territories of present-day Zimbabwe, to hit the Matabele and Shona in 1896. Used in World War II (1939–1945), it became more known in the Vietnam War, used by the United States (Project Eldest Son), and recently in the Syrian War. The use of spiked ammo is part of what is called unconventional warfare.

The simultaneous explosion of pagers and walkie-talkies inaugurated a new stage in the capitalist necrotechnological race because it revives old electronic warfare at a new level that combines interference in the device’s production chain with social and logistical engineering. This allowed the altered devices—whose components were produced in different countries—to reach the targets and explode at the desired moment. It is suspected that the bombs were triggered by a radio signal emitted by Hezbollah’s own command. The connection of this signal with the explosive outcome still needs to be studied but already points to new possibilities of orchestrated deaths by the great capitalist powers.

What Lessons Can We Draw from This Event?

If in times of peace the dependence on foreign technology, within the frameworks of imperialism and digital colonialism, directly harms national sovereignty and the self-determination of peoples, now we explicitly know the threat of this dependence during war. The warlike-technological race is not limited to software but also occurs in terms of hardware. Let us not forget the most instructive phrase of Google’s then leaders, Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen: “What Lockheed Martin was to the twentieth century, technology and security companies will be to the twenty-first century” (Cf. Assange, 2015, p. 40), declaring the new geopolitical role of big techs.

Electronic warfare, cyber warfare, and these new “unconventional” attacks have their materiality, permeated by the spheres of capital production and circulation, their logical chains, and “shadow” companies that apparently barely know what subcontractors do in their name. The hardware logistics chain of electronic components requires means of production—that is, raw materials, tools, labor, and the digital cloud that can only exist through this process. For the ethereal digital cloud to exist, it is necessary to emit steam from the cooling needed to contain the overheating of processors and boards.

Among the fantasies of our time is the denial of the ubiquity of capital and the materiality implicit in the sociometabolic mode of reproduction. According to some prominent intellectuals, the capitalist mode of production is experiencing a kind of neo-feudal regression, or techno-feudalism that profits from value through the monetization of intangibles or in circulation itself—inviting Marxists to abandon “factory thinking.” However, as Terezinha Ferrari argues, the factory has not ceased to exist but has expanded, manufacturing the city and increasingly substantial fractions of private life (Faustino, Lippold, 2023).

Ferrari argues that the introduction of computerization and robotics in the capitalist production process allowed not the much-talked-about overcoming of the Fordist production line but the synchronization of social work times to enable the articulation of different productive units in a geographical context where public roads are converted into open-air production lines. Not by chance, the quintessential ideological slogan of the fabricalization of the city is the famous “Just in time” created by Toyota Motor Corporation in the 1940s and 1950s, adopted as an ideological mantra of flexible accumulation. The explosions in Lebanon and Syria, in a kind of fabricalization of war, seem to realize this mantra by inaugurating the just-in-time explosion. The event places us before the phenomenon of manipulation and social engineering of insurgency itself: Israel, with its technological vanguard in digital surveillance, along with the conditions of the Lebanese power grid, led Hezbollah and civilians to circumvent the use of cell phones, reverting to devices like pagers and walkie-talkies. To what extent all this was part of the plan, only time will tell. But the case raises the alert to the complexity of the technical and social means employed.

Notes:

[1] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce9jglrnmkvo

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/18/world/middleeast/lebanon-funeral-pager-attack.html

[3] https://www.theweek.in/news/world/2024/09/18/lebanon-panic-as-two-solar-panel-systems-explode-amidst-pager-walkie-talkie-blasts-in-beirut-targeting-hezbollah.html

[4] https://www.boitempoeditorial.com.br/produto/colonialismo-digital-152312

[5] See the website of the necrocorporation IAI. The diversification of the war arsenal in the company’s catalog is impressive. https://www.iai.co.il/

[6] Intelligence division of the Israeli armed forces, similar to the NSA but military; the same that created Stuxnet.

[7] A technological innovation that recalls the Algerian sophistication against the French army, when the military engineering of the National Liberation Front of Algeria reorganized its structure so that each member would only communicate with and know a very limited number of militants (in case they were captured and tortured, they wouldn’t have much information to give).

[8] https://apnews.com/article/hungarian-company-behind-lebanon-pager-explosions-9ebcca9cc9e5a7d7bc9bc74ddcf23fb3

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/18/world/europe/pager-explosions-lebanon-what-we-know.html

[10] https://www.newindianexpress.com/world/2024/Sep/18/gold-apollo-says-pagers-that-exploded-in-lebanon-syria-were-made-by-company-in-budapest

[11] https://www.infomoney.com.br/mundo/como-filme-de-espioes-israel-teria-adulterado-pagers-para-explodir-apos-mensagem/

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=joP7Tz2sbRE&feature=youtu.be&themeRefresh=1

References:

Assange, Julian. When Google Met WikiLeaks (trans. Cristina Yamagami). São Paulo: Boitempo, 2015.

Chamayou, Grégoire. Drone Theory. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2015.

Faustino, Deivison; Lippold, Walter. Digital Colonialism: For a Hacker-Fanonian Critique. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2023.

Ferrari, Terezinha. Fabricalization of the City and the Ideology of Circulation. São Paulo: Coletivo Editorial, 2008.

Racionais MC’s. Mano Brown. “Diary of a Detainee.” São Paulo: Cosa Nostra, 1997.

Silveira, Sérgio Amadeu da. “WikiLeaks and Control Technologies.” In: ASSANGE, Julian. When Google Met WikiLeaks (trans. Cristina Yamagami). São Paulo: Boitempo, 2015.

kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbetCall for Papers – SMAIAS-ASN Summer School 2025

Sovereignty and Solidarity in Late Neocolonialism

The SMAIAS/ASN Summer School brings together young and veteran researchers and activists from all continents, especially from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and provides for collective reflection and learning.

Interested researchers and activists are invited to submit paper proposals (abstracts) of up to 200 words, in English, no later than 18 August 2024. Proposals should be submitted via the online form here: bit.ly/3zpl7WS. Women are especially encouraged to participate.

The selection of proposals will be publicized by the end of August via our social media. The results will not be communicated individually. Please consult our social media below.

Authors of selected proposals will be invited to send their full papers by 3 January 2025. Kindly note that authors of selected proposals who do not send their full papers by this date will not be included in the final programme.

The Summer School will be held in hybrid (physical and virtual) format in the week of 3–7 February 2025, at the Sam Moyo African Institute for Agrarian Studies, in Harare, Zimbabwe. Funding for physical participation is limited. Participants who wish to join physically in Harare are encouraged to access own institutional funding.

Call for papers

kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbetImperialismo e a situação neocolonial tardia

Paris Yeros and Luccas Gissoni

O desafio que temos diante de nós é compreender as realidades das formações sociais nas periferias da economia mundial com o propósito de iluminar o caminho da transição socialista. Este desafio tem pelo menos dois aspectos inter-relacionados. O primeiro exige que avaliemos a evolução da correlação de forças em torno da contradição principal entre o imperialismo e o povo trabalhador no terceiro mundo. Esta não é uma tarefa simples, tendo em conta a evolução contínua do imperialismo, por um lado, e das forças anti-imperialistas, por outro. Abordaremos brevemente alguns aspectos dessas questões. A segunda é identificar as trajetórias e legados das situações coloniais na etapa neocolonial tardia. Isto deverá fornecer-nos uma perspectiva adicional sobre questões políticas concretas.

A situação neocolonial tardia

Ao analisar a evolução do imperialismo, devemos considerar as contradições reais sobre as quais este tem exercido o seu domínio. Tal como concebido por Lenin (1984[1916]), na fase do capitalismo monopolista, o imperialismo elevou o modo de produção capitalista ao seu estágio superior, em razão do alto grau de concentração e centralização do capital, do modo de apropriação de rendas específico aos monopólios e da intensificação das contradições internas e externas que lhe correspondem. Elaborações posteriores buscaram especificar as condições de funcionamento do sistema de monopólios numa fase ainda mais concentrada e com tendência à estagnação (Baran & Sweezy, 1966). Na virada do século XX, no entanto, como bem observou Lenin, as contradições fundamentais ainda se moviam em torno de uma intensa e expansiva rivalidade interimperialista e uma renovada expansão colonial.

O estágio superior naquela fase não era idêntico ao “último” estágio em suas condições objetivas e subjetivas. A última fase do imperialismo foi alcançada justamente na segunda metade do século XX, na conjuntura de incipiente estagnação paralelamente ao processo geral de descolonização e transição neocolonial, tal como concebida por Kwame Nkrumah (1967[1965]). Esta tem sido a última fase porque as contradições inauguradas pelos movimentos anticoloniais elevaram a luta de classes em escala global ao nível de conflito direto com o sistema político colonial, isto é, o sistema político básico do capitalismo histórico. Nesta etapa, os movimentos anticoloniais puseram fim ao sistema colonial em geral e globalizaram o princípio da autodeterminação nacional.

A descolonização geral não pôs fim ao imperialismo, nem a todas as situações coloniais, mas abriu caminho à uma nova fase da luta de classes nas situações coloniais remanescentes. Ao mesmo tempo, no mundo neocolonial, emergiu uma competição mais abrangente e acirrada entre forças internas e monopólios estrangeiros. Estas contradições foram agravadas, como também observou Nkrumah, pela competição nuclear iniciada pela Guerra Fria, que desencadeou novos e graves perigos.

Samir Amin nos forneceu um conjunto de formulações sobre a trajetória desta fase moribunda do capitalismo. Amin argumentou que a descolonização reproduziu os padrões de desenvolvimento desigual herdados do sistema colonial, mas num novo nível de contestação em que as estratégias nacionalistas burguesas e socialistas competiam pela liderança sobre a modernização das novas nações (Amin, 1976[1973], 1981, 1986, 1990[1985]). Apesar das aparências, isto não consistiu numa “expansão capitalista”, mas em lutas por uma nova ordem que ameaçava o imperialismo. No entanto, a luta anti-imperialista nesta fase foi dificultada pelas fragilidades internas das forças burguesas e populares e agravada pela Guerra Fria, que se tornou, na realidade, uma Terceira Guerra Mundial, dada a escala da agressão imperialista contra os movimentos de libertação em todos os cantos do sul. Isto acabou por levar à compradorização das burguesias e à derrota ou ao isolamento das transições socialistas. Mas, ainda assim, esta foi uma vitória de Pirro para o imperialismo, dado que levou à obsolescência do capitalismo como modo de produção, tornando-o incapaz de evitar o seu próprio desaparecimento histórico (Amin, 1990[1985], 2003).

A nível econômico, o capitalismo monopolista, em sua avançada concentração e centralização, não conseguiu sustentar a absorção dos seus excedentes num ciclo virtuoso de produção e consumo. Após o início da crise em 1966, o ataque aos salários e rendimentos no centro e na periferia reforçaria a trajetória de declínio. Como também demonstram Patnaik e Patnaik (2016), essa contradição à escala mundial continuou a girar em torno do valor da moeda-chave do mundo, cuja âncora permaneceu sendo as mercadorias primárias produzidas no terceiro mundo. O maior consumo próprio dos produtos primários, tal como pretendido pelas políticas desenvolvimentistas no sul recém-independente, acabou por ameaçar o valor da moeda mundial e, portanto, as margens de lucro no norte. Por outro lado, a imposição de um consumo reduzido na periferia após a década de 1980, tal como antes da descolonização, pretendia restaurar os níveis de preços e lucros no centro, mas à custa especialmente do povo trabalhador do terceiro mundo.

Amin (2018, 2019) argumentou que a nova correlação de forças em torno desta contradição principal abriu caminho para que o capitalismomudasse para uma nova estrutura caracterizada pela generalização dos monopólios e pela financeirização. Nela, a renda imperialista poderia ser reforçada pela globalização da produção e expansão dos lucros financeiros, enquanto os monopólios avançavam contra todas as atividades, a montante e a jusante, em todos os setores. Com efeito, foi inventado um sistema especificamente neocolonial para a drenagem da riqueza, baseado numa nova rodada de superexploração do povo trabalhador e dos seus recursos naturais e energéticos, e no desvio das poupanças do mundo para o nexo dólar-Wall Street. O imperialismo permaneceu no formato triádico da aliança estratégica liderada pelos EUA com a Europa e o Japão e expandiu o seu controle sobre os pontos estratégicos da economia mundial. Mas, uma vez mais, ele não conseguiu evitar a crise nem escapar ao seu destino. Isto também explica o contínuo aumento de capacidades militares como uma solução econômica e política necessária e a expansão agressiva das bases militares e do intervencionismo no leste e no sul.

A tese geral acerca da contradição principal é inabalável, mesmo que se deseje elaborar ou ajustar aspectos dela. Yeros e Jha (2020) têm argumentado, neste sentido, que esta última fase do imperialismo implicou numa transição de uma fase “inicial” do neocolonialismo, ainda disputada por Estados nacionalistas no espírito de Bandung, para uma fase “tardia”, marcada pela consolidação do neocolonialismo no decurso da crise permanente do capitalismo monopolista. Esta situação neocolonial tardia, correspondente ao período da hegemonia neoliberal, sobrevive há quase cinco décadas.

A questão óbvia diz respeito à intensificação da luta anti-imperialista mais uma vez. Esta provém de diversas fontes, incluindo a emergência global da China sob o socialismo de mercado, a re-radicalização do nacionalismo do terceiro mundo (Irã, Venezuela, Iêmen, Zimbábue, entre outros), o confronto militar da Rússia com a OTAN e a luta armada do eixo de resistência contra o sionismo (Yeros, 2024). Mas estas questões não têm respostas evidentes e certamente não podem ser tratadas superficialmente em termos de “ciclos sistêmicos” ou “política de poder”, como a ciência política imperialista nos quer fazer acreditar. Devemos tirar as conclusões corretas relativamente à correlação de forças nas condições específicas do neocolonialismo tardio e ao sentido da mudança que é necessária para o povo trabalhador do terceiro mundo.

Em primeiro lugar, devemos concluir que o capitalismo monopolista é incapaz de resolver as suas contradições subjacentes de acumulação sem a presença do sistema colonial que manteve o capitalismo em pé durante séculos. As observações acima e posições previamente publicadas são suficientes para nossos propósitos atuais. Em segundo lugar, esta longa fase de decadência sistêmica persistirá até que se enraíze uma transição generalizada para o socialismo. Nem as teorias da “política de poder” (Mearsheimer, 2007), nem dos “ciclos sistêmicos” (Arrighi, 1996; Arrighi & Silver, 2001) – que são essencialmente teorias imperialistas, não teorias do imperialismo – podem apreender a realidade de um sistema moribundo: não haverá novo ciclo para o capitalismo monopolista; não há solução para a política de poder sem o poder popular. Nem, de facto, podemos recorrer a noções puras de “taxa de lucro decrescente” de um “capitalismo em geral” (Roberts, 2016), que também está em voga nos centros imperialistas, para compreender a crise do imperialismo.

Terceiro, a vingança imperialista contra o emergente terceiro mundo criou uma armadilha histórica que pesará fortemente nas transições socialistas no século XXI. A integração das forças produtivas da periferia nos sistemas globais de valor dominados pelos monopólios procedeu com base numa nova e longa ronda de acumulação primitiva. Embora a desconexão da lei do valor (Amin, 1990[1985]) seja, em algum grau, sempre possível, a verdadeira armadilha é o enorme tamanho das reservas de trabalho que foram criadas nesta fase do neocolonialismo tardio (Jha et al., 2017; Jha & Yeros, 2021, 2022, 2023; Yeros, 2022). Ao lado da compradorização das burguesias, elas subvertem estruturalmente o exercício da soberania a partir de dentro. Hoje, não é apenas a fraqueza das burguesias e das forças populares que minam a capacidade de resistir, mas também a profunda polarização política e o avanço de tendências fascistas. Assim, a desconexão da lei do valor com orientação soberana e popular confronta, atualmente, uma formação social diferente daquela da década de 1960. A contradição é ainda agravada no presente século pela mudança climática e pelos fenômenos extremos que atingem o povo trabalhador nas reservas de trabalho. Esta armadilha histórica é o ponto de partida concreto da transição socialista no século XXI e deve ser enfrentado diretamente.

Finalmente, vale a pena reiterar que o neocolonialismo como etapa histórica não deve ser confundido com o colonialismo. A teoria do colonialismo voltou a ocupar o pensamento social nos últimos anos, porém com tendência, especialmente em variantes do tipo “decolonial”, a abstrair-se das fases do capitalismo e até a restringir o significado das lutas populares. A descolonização foi um momento decisivo na história do capitalismo, impulsionada por uma força social inteiramente nova à escala mundial, composta por camponeses, trabalhadores e burguesias emergentes, que pôs fim precisamente ao sistema colonial, o sistema político natural do capitalismo. O neocolonialismo deslocou o eixo global da luta de classes contra o capitalismo monopolista, inclusive em relação às questões coloniais e semicoloniais não resolvidas. Ademais, a descolonização foi um momento decisivo porque seguiu os passos da Revolução Bolchevique, a qual abriu o caminho a um novo nível da luta mundial da classe trabalhadora e do campesinato. As duas revoluções – a socialista e a anticolonial – eclodiram em sinergia histórica. Os comunistas chineses entenderam-no assim:

Ocorreu uma transformação na revolução democrático burguesa da China, depois da irrupção da primeira guerra imperialista mundial e da construção do Estado socialista na sexta parte do mundo, com a vitória da Revolução Russa de Outubro de 1917.

Antes disso, a revolução democrático-burguesa chinesa pertencia à categoria da velha revolução democrático-burguesa mundial e dela fazia parte. A partir daquela época, a revolução democrático-burguesa chinesa tem modificado o seu caráter e pertence agora à categoria da nova revolução democrático-burguesa. No que diz respeito à frente revolucionária, ela é uma parte da revolução socialista-proletária mundial.

Por que? Porque a primeira guerra imperialista mundial e a vitoriosa Revolução Socialista de Outubro modificaram a trajetória do mundo, traçando uma nítida linha divisória entre as duas etapas históricas (Mao, 2006[1940], n.p.).

Abstrair-se da fase histórica do neocolonialismo tardio acaba restringindo as lutas anti-imperialistas e anticoloniais à busca do refúgio numa situação neocolonial “mais humana”, o que é historicamente insustentável. Não só temos atrás de nós um século de experiências socialistas e desenvolvimentistas que colocam as lutas contemporâneas num novo patamar objetivo e subjetivo, mas também temos diante de nós a realidade do socialismo de mercado chinês que alavancou de forma única na economia mundial para colocar em xeque ao imperialismo no curso de sua decadência.

Trajetórias de situações coloniais

Um outro conjunto de questões que requer atenção é o destino das situações coloniais remanescentes na fase do neocolonialismo tardio. Ao longo de meio milênio de capitalismo, o domínio colonial assumiu três formas gerais: colônias de povoamento europeu, colônias de exploração (ou de conquista) e semicolônias. Todas elas foram colocadas na defensiva em meados do século XX, sendo sua maioria desmantelada em seguida. A ONU ainda conta dezessete “territórios não autônomos” – Sahara Ocidental, Gibraltar e várias ilhas do Caribe, do Atlântico e do Pacífico – mas esta lista, claramente, está incompleta. Em geral, as colônias de exploração na Ásia e na África foram as primeiras a conquistar a independência durante os “ventos da mudança” do pós-guerra. Algumas transitaram diretamente para o domínio neocolonial, enquanto os mais resistentes entre os Estados aderentes ao espírito de Bandung alinharam-se aos interesses do imperialismo numa fase posterior, quer às vésperas da etapa neocolonial tardia (por exemplo, o Egito), quer no decurso da mesma (por exemplo, a Índia).

Uma questão relacionada, no entanto, é a situação semicolonial à qual sucumbiram algumas dessas ex-colônias. O semicolonialismo baseia-se em formas mais intensas de acumulação primitiva relacionadas à tomada parcial de território pela guerra agressiva, à imposição de tratados desiguais, ao estacionamento de forças militares e ao exercício da jurisdição consular dentro do território ocupado (Mao, 1975[1952]; Yeros & Jha, 2020, p. 88). Indiscutivelmente, os países francófonos da África Ocidental viveram à beira desta situação semicolonial – como sugere o termo “Françafrique” – dado o grau excepcional de tutela econômica e militar direta que continuaram a sofrer após a descolonização (Pigeaud & Sylla, 2024, no prelo). Os resultados das recentes revoltas nacionais e populares contra o imperialismo francês na região continuam incertos (Gissoni & Yeros, 2023). Em todo caso, a fragmentação em série de Estados no neocolonialismo tardio sob o peso do imperialismo – incluindo regiões da África (Oeste, Norte, Centro, Sahel e Chifre), a região Oeste da Ásia e o Afeganistão, e o Caribe, especialmente o Haiti – expandiu a situação semicolonial de hoje para uma série de Estados que sofreram estes resultados mais extremos das contradições do neocolonialismo tardio (Moyo & Yeros, 2011).

As colônias de povoamento europeu, por sua vez, constituem uma categoria histórica própria, embora, como nos outros casos, existam trajetórias diversas entre elas. Há aqueles países, por um lado, que se tornaram centros do capitalismo monopolista (Estados Unidos, Canadá, Austrália), enquanto outros permaneceram dependentes dos centros imperialistas, passando da tutela do Reino Unido à dos Estados Unidos. A maioria destas experiências tem origem na primeira longa vaga de expansão colonial europeia nas Américas até o século XVIII, enquanto outras na África, no Pacífico e na Palestina sucumbiram posteriormente em momentos distintos. Nessa mesma conjuntura, as experiências americanas anteriores começaram a separar-se das metrópoles europeias, mas apenas uma, o Haiti, rompeu com o colonialismo de povoamento, permanecendo o restante das Américas num modo de acumulação e dominação colonista até as últimas décadas do século XX. Harry Haywood (1933, 1948) proporcionou a primeira análise robusta desta questão nos marcos do marxismo-leninismo, concebendo-a como uma espécie de “colonialismo interno”, dentro do centro imperialista.

As colônias de povoamento dependentes e de enclave na América Central e no Caribe sofreram repetidas intervenções imperialistas, não menos em função da fragilidade dos colonos locais, e foram rebaixadas a uma situação semicolonial. Esta condição ocorreu ao longo dos séculos XIX e XX e continua a ser uma ameaça constante na atual fase do neocolonialismo tardio. Mas aqueles que escaparam à situação semicolonial permaneceram no modo de acumulação colonial interna e dependente sob o domínio direto de colonos europeus. A transição do colonialismo de povoamento para o neocolonialismo na América Latina permaneceu espasmódica, com frequentes imposições de ditaduras militares. Mesmo a revolução no México permaneceu limitada, apesar do novo grau de soberania obtido, dado o atraso do sufrágio universal e as suas próprias contradições raciais. Cuba foi a única experiência de rebelião efetiva contra tanto o colonialismo de povoamento como a transição neocolonial, em meados do século, através da revolução socialista.

No geral, estas colônias americanas de povoamento europeu, apesar da sua precoce separação jurídica das metrópoles, mantiveram as estruturas de acumulação e as relações de classe herdadas da colonização europeia. Portanto, os povos colonizados da região evoluíram em conjunto com as lutas no resto do mundo colonial, e em sinergia, no século XX, com as lutas socialistas, anti-imperialistas e anticoloniais. Todas essas lutas convergiram em meados do século XX. As colônias de povoamento dependentes da América Latina fizeram geralmente as suas transições para o neocolonialismo já no período tardio deste, paralelamente às transições na África Austral, com a consolidação do sufrágio universal a partir dos anos 80. Na maioria dos casos, e no caso do Brasil especificamente, um quadro neocolonial mais arraigado, tornado possível pelo capitalismo monopolista em vias de financeirização, foi a pré-condição para uma transição neocolonial aceitável aos próprios colonos (Yeros et al., 2019; Yeros & Jha, 2020; Gissoni et al., 2024, no prelo).

Até hoje, o colonialismo de povoamento e os seus legados cumprem funções cruciais para o imperialismo. As restantes colônias de povoamento plenamente em vigor são locais importantes de extração de mais-valia e de exploração de recursos naturais em seu território, como acontece com a indústria mineira de níquel na Nova Caledônia e, acima de tudo, com o Estado sionista no mundo árabe, onde os recursos energéticos e outros interesses estratégicos são primordiais. Elas são ainda mais importantes dada a crise permanente do capital monopolista e o impasse neocolonial tardio. Além disso, as alianças internacionais construídas em torno dos interesses dos colonos são fundamentais para as tendências fascistas que estão mais uma vez avançando no decurso da crise. No passado, os interesses dos colonos cerraram fileiras com o imperialismo na América do Sul e na África Austral (Yeros et al., 2019; Lobato, 2017; Marangoni, 2018; Gissoni et al., 2024). É evidente que hoje foram remobilizados de um continente para outro em direção ao Estado sionista em defesa do genocídio dos palestinos.

A história do colonialismo é recente e o seu fim está em curso. A descolonização geral é, fundamentalmente, a base política da crise permanente do imperialismo, que vemos hoje no período neocolonial tardio, em toda a sua barbárie.

Referências

AMIN, S. (1976[1973]). O Desenvolvimento Desigual. Rio de Janeiro: Forense-Universitária.

AMIN, S. (1981). Classe e Nação na História e na Crise Contemporânea. Editora Moraes.

AMIN, S. (1986). O Futuro do Maoísmo. Editora Vertice.

AMIN, S. (1990[1985]). Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World, trans. M. Wolfers. Londres & Nova Jersey: Zed Books.

AMIN, S. (2003). Obsolescent Capitalism. Londres & Nova York: Zed Books.

AMIN, S. (2018). A Implosão do Capitalismo. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ.

AMIN, S. (2019). The New Imperialist Structure. Monthly Review, 71(3), https://monthlyreview.org/2019/07/01/the-new-imperialist-structure/.

ARRIGHI, G. (1996). O Longo Século XX. RJ: Contraponto.

ARRIGHI, G., & SILVER, B. J. (2001). Caos e Governabilidade no Moderno Sistema Mundial. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto.

BARAN, P. & SWEEZY, P. (1966). Capitalismo Monopolista. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Zahar.

GISSONI, L., PIRES, P. R. M. S. O. & CARVALHEIRA, L.G. (2024, no prelo). Development Paths in a Colonist Society: The Challenges of the Communist Movement in Brazil. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 13(2).

GISSONI, L. & YEROS, P. (2023). Níger: Neocolonialismo e Questão Nacional no Sahel. Portal Grabois, https://grabois.org.br/2023/08/31/niger-neocolonialismo-e-questao-nacional-no-sahel/.

HAYWOOD, H. (1933). The Struggle for the Leninist Position on the Negro Question in the USA. The Communist, 12(9), 888–901, www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v12n09-sep-1933-communist.pdf.

HAYWOOD, H. (1948). Negro Liberation. Nova York: International Publishers.

JHA, P., MOYO, S., & YEROS, P. (2017). Capitalism and ‘labour reserves’: A note. In C. P. Chandrasekhar & J. Ghosh (Eds.), Interpreting the world to change it: Essays for Prabhat Patnaik (pp. 205–237). New Delhi, India: Tulika Books.

JHA, P. & YEROS, P. (2021). Labour Questions in the Global South? Back to the Drawing Board, Yet Again. In: JHA, P., CHAMBATI, W. & OSSOME, L. (Orgs), Labour Questions in the Global South (pág. 19–48). Singapura: Palgrave Macmillan.

JHA, P. & YEROS, P. (2022). The World of Work in an Age of Permanent Crisis. Economic and Political Weekly, 57(42), 39–45, Nova Déli.

JHA, P. & YEROS, P. (2023). Rural-urban Circuits of Labour in the Global South: Reflections on Accumulation and Social Reproduction. In: ATZENI, M., APITZCH, U., MOORE, P., MEZZADRI, A. & AZZELLINI, D. (Eds), Handbook of Research on the Global Political Economy of Work (pág. 136–146). Cheltenham & Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

LENIN, V.I. (1984[1916]). O imperialismo, fase superior do capitalismo. Obras Escolhidas, Tomo 2. Lisboa-Moscovo: Editorial Progresso, www.marxists.org/portugues/lenin/1916/imperialismo/index.htm.

LOBATO, G. (2017). The strange case of Brazilian support to the FNLA in the final stage of Angolan decolonization (1975). Afriche e orienti: Rivista di studi ai confini tra Africa Mediterraneo e Medio Oriente, 19(3), 31–48.

MAO T-T. (2006[1940]). A Nova Democracia na China. www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_26.htm.

MAO T-T. (1975[1952]). A Revolução Chinesa e o Partido Comunista da China, www.marxists.org/portugues/mao/1939/12/revolucao.htm.

MARANGONI, P. (2018). A Opção pela espada: os comandos especiais na linha de frente em defesa do mundo ocidental. Clube de Autores.

MEARSHEIMER, J. (2007). A Tragédia da Política das Grandes Potências. Editora Gradiva.

MOYO, S. & YEROS, P. (2011). The Fall and Rise of the National Question. In: MOYO, S. & YEROS, P. (ORgs), Reclaiming the Nation: The Return of the National Question in Africa, Asia and Latin America (pág. 3–28). Londres: Pluto Press.

NKRUMAH, K. (1967[1965]). Neocolonialismo: Último estágio do imperialismo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

PATNAIK, U., & PATNAIK, P. (2016). A Theory of Imperialism. Nova Déli: Tulika Books.

PIGEAUD, F. & SYLLA, N. S. (2024, no prelo). The Revolt Against Françafrique: What Is Behind the ‘Anti-French’ Sentiment? Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 13(2).

PRASAD, A. & YEROS, P. (2024). Patriarchy and the Contradictions of Late Neo-colonialism. In: TSIKATA, D., PRASAD, A. & YEROS, P. (Orgs), Gender in Agrarian Transitions: Liberation Perspectives from the South (pág. 3–28). Nova Déli: Tulika Books.

ROBERTS, M. (2016). The Long Depression. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

YEROS, P. (2022). Semiproletarização Generalizada na África. Revista Princípios, 165 (set./dez.), 97–125.

YEROS, P. (2024). A Polycentric World Will Only be Possible by the Intervention of the “Sixth Great Power”. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 13(1), 14–40 [Um Mundo Policêntrico Só Será Possível pela Intervenção da “Sexta Grande Potência”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379022939_Um_Mundo_Policentrico_So_Sera_Possivel_pela_Intervencao_da_Sexta_Grande_Potencia]

YEROS, P. & JHA, P. (2020). Late Neo-colonialism: Monopoly capitalism in Permanent Crisis. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 9(1), 78–93 [Neocolonialismo Tardio: Capitalismo Monopolista em Permanente Crise, www.agrariansouth.org/2020/05/27/neocolonialismo-tardio-capitalismo-monopolista-em-permanente-crise/

YEROS, P., SCHINCARIOL, V.E. & SILVA, T.L. (2019). Brazil’s Re-encounter with Africa: The Externalization of Domestic Contradictions. In: S. MOYO, P. JHA, & YEROS, P. (Eds.), Reclaiming Africa: Scramble and Resistance in the 21st Century (pág. 95–118). Singapura: Springer.

kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet kampungbet- Published in Our Blog

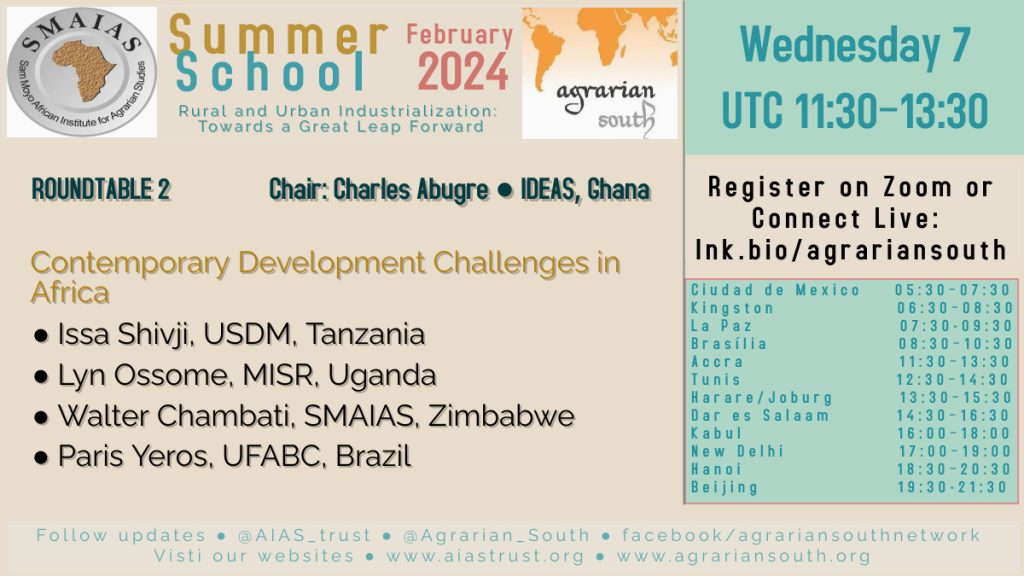

SMAIAS-ASN Summer School 2024

We are very pleased to invite you to our SMAIAS-ASN Summer School 2024, which will take place in the week of 5-9 February, in Harare and online, in hybrid format. The theme this year is “Rural and Urban Industrialization: Towards a Great Leap Forward”.

We are honoured to have with us this year Professor Jayati Ghosh, who will deliver the 7th Sam Moyo Memorial Lecture, on Tuesday, 6 February. The title of the lecture will be “Development in the Time of Climate Imperialism: How Can the Global Majority Cope?”

The Full Programme with details on panels, roundtables, and the Sam Moyo Memorial Lecture is available below. Links to Zoom and Livestream also appear below.

Links & Zoom registration

MONDAY 5th

Roundtable 1: Zoom 🔗∙ YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

Panel 1: Zoom 🔗

TUESDAY 6th

Panel 2: Zoom 🔗∙ YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

7th Sam Moyo Memorial Lecture: Zoom/YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

WEDNESDAY 7th

Roundtable 2: Zoom 🔗∙ YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

Panel 3: Zoom 🔗

THURSDAY 8th

Roundtable 3: Zoom 🔗∙ YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

Panel 4: Zoom

FRIDAY 9th

Roundtable 4: Zoom 🔗∙ YouTube/Facebook Live lnk.bio/agrariansouth 🔗

Panel 5: Zoom 🔗

Programme

Sam Moyo Memorial Lecture

Panels

Roundtables

Papers

BERNARDO SCHIRMER MURATT – Neo-developmental Misery: FIESP in the 2016 Brazilian Coup d’État 🔗

DINESH ABROL – Path Formation for Rural Industrialization in India: Lessons for Peoples’ Democracies 🔗

FADZAI MHARIWA – Renewable Energy Consumption and Gender Development in Southern Africa (2002–2020)

MATHEUS MOREIRA – The Role of Small Tech in the Concentration and Centralization of Capital 🔗

NEWMAN TEKWA – Land Reform and Industrial Development in Mexico: Practical Lessons for Zimbabwe 🔗

RAKHEE KEWADA – Technology and Underdevelopment in Tanzania’s Cotton and Textile Sector 🔗

SEMHAL ZENAWI – Dirge for the Ethiopian Left 🔗

TAHIRÁ ENDO GONZAGA – Angola’s Trajectory and Development Challenges in the 21st Century 🔗

ZEYAD EL NABOLSY – Paulin Hountondji on Dependency Theory and Technology 🔗

Candidates for Samin Amin Prize 2022-23

Samir Amin Young Scholars’ Prize in Political Economy of Development

Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, Volumes 11–12 (2022–2023)

Candidates:

- Asymmetry and Unequal Exchange in the Agricultural Value Systems: Case Study of Paddy – MANISH KUMAR

- Theories of Political Ecology: Monopoly Capital Against People and the Planet – MAX AJL

- The Role of Prevailing Agrarian Relations in Lower Crop Productivity and Profitability: Evidence from Uttar Pradesh, India – SHINU VARKEY

- The Legacy of Clóvis Moura: A Marxist Critique of Race in Brazil – WEBER LOPES GÓES

More information on the prize and other editions can be found here.

ASN Research Bulletin: Special Issue on Palestine

http://www.agrariansouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ASN-RB-Nov_-Dec-2023_Final.pdf

ASN Research Bulletin_Nov to Dec Special Issue on Palestine

http://www.agrariansouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ASN-RB-Nov-Dec-2023-1.pdf

Petition: Stop the Genocide!

Sign the petition HERE✍🏼

STOP THE GENOCIDE! FREE PALESTINE!

The Agrarian South Network adds its voice to the condemnation of the genocide being perpetrated by the Zionist state against the Palestinian people with the backing of the United States and the European Union.

It is unacceptable that a settler colonial state continues to exist and that it is allowed to practice apartheid and carry out the extermination of the people it occupies.

It is unacceptable that the imperialist war machine of the West is once again unleashing its full force against an oppressed people of the South.

The NATO-Zionist alliance is entirely responsible for the violent confrontation in Palestine.

We express our unconditional support to the struggle of the Palestinian people for freedom and justice.

We call on our governments to break ties with the Zionist state and confront imperialism.

This is the defining moment of the 21st century. Imperialism and colonialism must be defeated once and for all.

LIST OF SIGNATURES (Dec. 18th 2023) HERE: